|

My Arrest and Imprisonment

CHAPTER 11 One of the rehearsals of Gleser's drama studio took place in a school building located on the corner of Gogol St. and what was then the Church of Jesus. It must have been the end of May. Suddenly the police came, which was not such a rarity then. They started searching the place and recording the names of the people present. One of the policemen suddenly called out: "Whose bag is that?" It was my schoolbag, it was no use denying it as it had in it books and notebooks bearing my name and surname. Apart from my books and notebooks it also contained - I realized that immediately - a bunch of small leaflets calling to protest against the exhausting examinations held in bourgeois schools (there were no examinations at all in Soviet schools at that time). I also realized quickly enough that I cannot deny that it was my schoolbag, but I can deny any knowledge of those leaflets. This was exactly what I did. When the policeman showed me those leaflets I looked very surprised and said they do not belong to me and I had no idea how they found their way into my bag. Maybe someone had put them in my bag at school, since I did not go home after school and came straight from there to the rehearsal. From that very day until the last day of the investigation I kept repeating the same story: "After classes we went down, as usual, to the school yard to play ball. I left my bag under a tree and went off to play. We stayed in the school yard for quite a long time. Then I took my bag and went to the rehearsal. I did not open it either in the yard or here, during the rehearsal. I don't know anything about these leaflets and I don't know who had put them into my bag." After the search and the registration of our names the police let most of the studio members go home, while I and a few others were taken down to the police station in Gogol Street. We were kept there till late in the evening and then taken to the offices of the political administration (the so-called "Okhranka") in Albert Street (now Fritzis Gailis Street). I spent the night in a very tiny room. Later I found out that this was the punishment cell. In the morning I was transferred to a "solitary" cell: it was a large room with a metal bed that was fastened to the wall and raised back during the day. There was also a table and a chair. The door had a special peephole for the guards, so that they could watch the inmates from time to time.

My life at the "Okhranka" offices lasted about three days. Time passed very slowly as I was not allowed to have any books or any paper and a pencil. I found the "prison alphabet" on the wall and learned it, so I could communicate with my neighbors, other prisoners, by these series of knocks. I also made some chess figures by using some of the bread I got. It worked out quite well, but I still suffered because I did not have anything to occupy myself with. I have always found idleness hard to bear. Every day they brought me in for questioning. I went back again and again to my version of the story: "After school we went down to play ball, as we usually did …" As I went on with my story I remembered how I got those leaflets and how I pasted most of them on walls at school, but something prevented me from finishing my job and I had about ten of them left. I put them into my bag. It was considered quite a transgression to destroy or throw out illegal stuff, so I decided to finish my job the next day. I could not have foreseen that the police would come to the studio rehearsal. It was the first time that the police came to our studio. One day, as I went on and on with my version, the interrogator started speaking in a dreamy voice: "Look at the blue sky, at the wonderful sunny day out there!" I kept agreeing with him about that. He went on: "Would not you like to be free, to see the trees and the flowers, to see your friends?..." I just nodded and looked at the window. "So, why don't you tell the truth? Where did you get those leaflets?" And I promptly went back to my story, word for word, as I did before. They took me back to my cell. Another time the interrogator tried to put pressure on me by telling me that Mother cried bitterly when she came to inquire about me. He kept assuring me that they will let me go as soon as I tell them what they wanted. I went back to my story. I also had an incident during those few days. One day one of the guards known as the "Gorilla" saw me knocking out a message on the wall of my cell, trying to communicate with the prisoner in the adjacent cell. He jerked the door open, looked at me threateningly, went up to me and pulled my hair, cursing me while doing so. And then he even hit my head against the wall. It was not really all that painful, but I started screaming very loudly. This was also something I had been told by my fellow underground activists: if you start screaming the prisoners in the surrounding cells will hear you and disturbances might start in prison. The guard let me go, pointing his threatening finger at me and saying that if he will catch me doing this once again I shall be in real trouble. I did not stop trying to pass on messages to my neighbors, but I was much more cautious and was not caught again. I remember having been warned at home in the past that if I ever get arrested it would create quite a difficulty: to supply parcels for two persons in prison would be an expense the family could hardly afford. Mother realized, without actually knowing anything definite, why I have been often absent from home. I used to reply to such warnings: "If I am ever arrested please do not send me anything and don't bring me parcels. I don't want to cause any more expenses at home." I understood that Mother spoke about financial problems only in order to dissuade me from engaging in underground activities. So now, after my arrest, when I received a parcel containing some bread, butter, meat patties and some other things, I sent back a note stating that I had received the parcel and expressing my gratitude. I also stressed that I did not need anything. Mother did send me a pillow and a blanket. They had enough experience with these matters at home… I spent a few days at the "Okhranka" premises. Then one day a guard came into my cell and ordered me to get my things ready and to put my coat on: I will be taken to the prison. I began to wait. I noticed that someone looked into the little window and then, after a while, the door opened and two huge policemen lead me along the corridor. I heard one of them saying to the other one, laughing: "We looked inside but did not even see her, she is as small as a mosquito!" I was standing near the door of my cell when they looked in and because I was so short they did not see me inside. Now, walking on both sides of me, someone who hardly reached their waistline, they kept pointing at me and sneering: "And now we have to take this to prison?!" We left the building and started walking along Elizabetes St. I was walking in the middle, holding a large parcel with my pillow, my blanket and my other things, and the two tall huge-looking policemen walked on my right and on my left, both of them carrying rifles. Much later someone told me that he saw me during this "parade procession". It was a very unusual picture! We walked that way down to Suvorova St. (later renamed Krishyan Baron St.) and then took a No. 2 tram that took us to its last stop: that was where the "temporary" prison was situated. This was a women's prison where women who had been arrested but not yet convicted were being held. In Prison At last we reached the prison. Screeching locks were unlocked, the door opened and we went inside. They lead me somewhere along a long wide corridor. The guard took out a large key, opened the door of the cell and went inside together with me. There was not too much light in the cell. A large group of women sat around a large table. For a moment there was complete silence in the cell and suddenly….everyone burst out laughing. The women laughed, the guard laughed and in the end I started laughing too. The laughter started because the picture was obviously a comical one: a little girl with her hair in plaits, wearing white tennis shoes and white socks, stood there holding a large parcel and next to her stood a huge guard with keys in his hand. The laughter lasted for a while and it stopped after the guard turned around and left, leaving me behind. All the women surrounded me and started asking me who I was, where was I from and why was I arrested. I have heard well before that from my Komsomol friends that when one finds himself in prison one has to tell his fellow prisoners the same things that he had told the interrogator: there have been cases when an agent-provocateur was placed in the cell where revolutionaries were held and it would have been difficult to expose him. So, I went back once again to my version of what must have happened to my schoolbag and how those leaflets got inside it. Everyone surrounded me and kept looking at me as if I were some strange object. Later on they said that I looked about 14 or 15 years' old. I did look like that even though I was nearly 18 at that time. Finally I took off my coat, put my things down and asked where could I wash myself. During the few days of my arrest at the "Okhranka" building washing was my biggest problem. There was only a water tap in some tiny room that was supposed to be the shower, but its door could not be locked and the guards did not leave the prisoners unguarded even during shower time. So, now I was a happy girl: they gave me a bowl of hot water, some soap and a bucket. I washed my hair and then washed the rest of me. What a wonderful feeling it was! Everyone admired my hair: it dried and fell on my shoulders in lovely thick waves. Someone said it would be a pity to have to cut it if I was to remain in prison and someone else said that it might be a good idea to cut it off right now. However, the others said that since it was not yet clear how my case would be resolved I should keep my hair as it is. Then I was allotted a plank bed to sleep on and I spent a night that seemed like heaven! The next morning was the beginning of the prison routine for me. After morning reveille we all went to wash. This took place in a special room where we all stripped and showered with cold water. Breakfast came afterwards. One of the women prisoners, the fat Anna, was in charge of the food and she gave out additional helpings from the common supplies (from the personal parcels the inmates received) to supplement our prison rations. Then we started our "lessons". Everyone had some plans of her own and I also started to read something and to make notes. I also clearly felt that something was going on around me but I had no idea of what it was. I learned while still "outside" that secret party cells were formed in prison, but one was not admitted right away. Usually some information about a new inmate was awaited from party or Komsomol members outside the prison. Since I was new and no information whatsoever was available about me it was still not possible to ascertain whether I spoke the truth, whether I was or was not a police agent, etc. I did become a member of the cell "collective", but no information about the secret underground work that took place near me was revealed to me. Something About My Fellow Inmates Of all the inmates I liked Lena Maizel best. She had a boyish haircut, an upturned nose, huge brown eyes and she reminded me either of a deer or little bear. I have never met her again. I did hear much later that she was working in some publishing house and was now quite old. There were also two pretty sisters, Marta and Berta Gaileh. They used to do morning exercises every morning…. I met Sonya Kovnat more than once later in life; she and our Dida were in the army together. I met Khana Skutelsky in Kirov during the war and we found ourselves attending the same course for party workers in 1942. I came across another two or three of the inmates later on. We once had an "amateur concert" in our cell: someone sang, someone recited poetry and I, after letting my hair down, danced a Russian dance and something called a "wild girl's dance", all this accompanied by the soft singing of the other women inmates. Back to the Routine From the prison I was taken in a closed car (which we called a "Black Bertha") for interrogation. Before being taken there I was taken to a small dingy room to await my turn to see the interrogator. The interrogation started with the usual questions about those leaflets, etc. and I kept repeating my usual version of what had happened. This was recorded, I signed the statement and was taken back to prison. The day when the inmates were allowed to receive parcels I received a parcel from home. Zyama brought it and I sent him a note stating that I had received it. I realized that it was not a good idea to refuse help from home since many of the inmates did not receive any parcels at all and whatever was received by others was divided equally amongst all the inmates of the cell. So, I did not write this time, as I had during my first few days of arrest, that there was nothing I needed. My life in prison did not last long: I spent three days in the "Okhranka" and then another eight days in prison. One day I was called to the prison office and told that I was being released from prison "under police supervision". This meant that twice a week until my trial I will have to report to the police station at a certain time of the day and sign the police record. I was also not allowed to leave Riga. Thus, one beautiful day I found myself outside the prison gates, unaccompanied by a police guard and holding my large parcel. I went home. I kept visiting the police station twice a week for about five months. There was no trial: my case was closed because of lack of evidence. My "version" which I had kept repeating again and again brought about positive results.

|

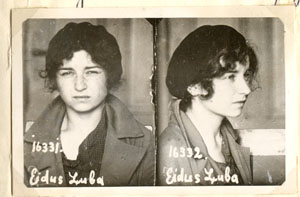

When they brought me to the "Okhranka" office

they had me photographed, as the procedure demanded. I remembered

having been told by fellow Komsomol members that in such cases I

should squint or pull a face so that later police followers would

not be able to identify me from my police photo. So, I tried to

squint and am now sorry I did: it would have been a nice picture.

When they brought me to the "Okhranka" office

they had me photographed, as the procedure demanded. I remembered

having been told by fellow Komsomol members that in such cases I

should squint or pull a face so that later police followers would

not be able to identify me from my police photo. So, I tried to

squint and am now sorry I did: it would have been a nice picture.