|

Moving to a Jewish School

CHAPTER 4 One day, when I was in Form 5, Mother met in the street a certain gentleman and spoke to him at length. She introduced me to him and to his wife and showed me their tiny little girl who was lying in her pram. After we parted she said that this was Mr. Zalmen Shneur, a teacher in the Jewish school, and his wife who was also a teacher. The little girl was their daughter Haveleh. In October this year, 1971, when I visited Eva Vater on the occasion of the October Revolution celebrations, I men Haveleh Vesterman, whose son, Vika, was by then a 2nd year medical student. The truth is that I have met Haveleh many times before: before the war I met both her and her sister Haneleh, when they were young girls, and later on, when she was already a doctor, a pediatrician specializing in problems of the adolescents, we have met again and I took Iren to see her. I have met her at Eva Vater's place many times before that. Her father Zalmen Shneur died at the front in the war. I am now going back to the school year 1926/27, when I was in Form 5. One day Mother took me to a theatre performance that took place at the Drama Theatre in Riga. It was called "Boom un'Dreidl" and it was staged by the Jewish School in Riga. I did not understand the language but I loved the dances, the decorations and the costumes. (It appeared that our Grandfather and Aunt Fanya were also taking part in that performance.) Afterwards Mother mentioned that she had been thinking of transferring me to the Jewish School. I protested: "Never!" During that period Mother was attending a teachers' course and she met many wonderful teachers. She also learned how well Jewish schools in Riga were run and she decided to transfer me and Zyama to such a school. It is possible that there were no tuition fees in the Jewish school, while the tuition fees in the private schools Zyama and I have been attending were very high. The family did not have much money during that year. After my categorical refusal to move to the Jewish school, Mother did not try to convince me, but she did speak about it from time to time. Suddenly, one day my opinion about moving to the Jewish school changed completely and that was when Mother mentioned something that attracted me immensely: it transpired that the Jewish school had a "drawing studio" and I will be able to attend it. Nothing could compete with drawing as far as I was concerned and I immediately agreed to move. I even used to ask impatiently when that will happen.

When I completed Form 6 and moved to high-school, I met Mr. Berkovich or Boya Berkovich, as he was known. There he was, finishing high-school that year. He was older than he was supposed to be in his final year of school, but so were many other students who, because of World War I, their years as refugees and other such events, missed out on school for a year or two. Boya Berkovich played a considerable part in my life some years later. It was Boya Berkovich ("Der Shwartzer" or "The Black One", as he was known) who recruited me to working with illegal Pioneer groups in the autumn of 1931, after all the Left-wing organizations and societies in Latvia were declared illegal. In June 1932, after my arrest, I spoke to him, requesting to put me in contact with the illegal "Komsomol" organization (the "Komsomol" was the Communist Party youth movement - Tr.) and to recommend me as a new member. Boya asked me then: "Will not it be too hard for you to work for the underground?" "Oh, no! I can do it!" - I replied. This conversation took place during a performance break in the Yiddish Theatre. (The Theatre was then housed in the building that now serves as the offices of the Communist Party Education Headquarters, at No. 6 Andreja Upisha St.) I have met "The Black One" several times during my underground activities: at one time he was in charge of Young Pioneer groups' activities (the Young Pioneers were the Communist Party's children's movement - Tr.), then he was in charge of a "propka", a propaganda group, of which I was a member. In 1940 he recommended me for membership in a propaganda activists' group affiliated with the Komsomol Central Committee. In 1940 Boya Berkovich recommended me as a candidate for Communist Party membership and later, after I was evacuated from Riga, for party membership. In 1945, at the time when I returned from evacuation in Russia, Boya Berkovich was the temporary Editor of the new Russian language newspaper "Sovetskaya Molodezh" ("Soviet Youth") and he took me on as a member of his editorial office. Back to 1927 When in the fall of 1927 Zyama and I went to the Jewish school for our entrance exam, we did not, of course, know Yiddish all that well, but we passed the exam, were accepted and right away started a "new life". It transpired that in city schools the study of arithmetic was completed in Form 5 while in private schools it was studied until the end of Form 6. I was therefore given time to prepare for the exam and sat for it separately… Soon enough I passed it. I was also lucky in another respect: I knew one of the girls in my class, she used to be in my rythmics' group. Her name was Luba Fishberg. A cheerful and capable girl, she took me "under her wing" right away. We shared a desk in class and became friends. We used to visit each other at home and we often did our homework together. One day we even had our picture taken together. We sat on a chair, our heads close together, my plaits were longer and thicker while Luba's were shorter but her hair was curly. We were both wearing shoes with shoelaces and we were both smiling. Luba smiled often. Her upper lip was a bit short and when she smiled that shorter lip made her smile look more cheeky. She smiled when called to the blackboard to answer the teacher's question and she smiled when returning to her desk. She found it hard to keep still. She did well in history and literature and she was good in other subjects as well; she knew "how to think". Luba was six months younger than me. Even though she was a clever girl, I still considered her "smaller". Luba had an older sister named Sima who was that year either finishing high-school or had one more year to go. I remember her once asking me what I was reading. I told her: Dostoyevsky's "Crime and Punishment". I had just started reading it. Sima looked at me seriously and said: "I think you should not be reading that book now. It is too early. You better wait for a couple of years." And I listened to her! I put Dostoyevsky's book away and started reading something else. When a few years later I went back to "Crime and Punishment" I recalled her good advice with gratitude. My "Independent" Birthday In mid-September 1927 I was invited by a boy called Fima Liven to his birthday: he turned 13 years' old. His whole class came. It was the first time ever that I went to visit someone whom my family did not know. I therefore decided that I shall also invite my whole class to my birthday and I shall also prepare my birthday party all by myself. Mother gave me some money (not too much!) with which I bought some cookies, sweets and apples and I also made some tea. My classmates came and I was very proud that for the first time I prepared my birthday party all by myself. Generally speaking, these two parties drew me closer to my classmates, but I still did not feel completely at ease. I was bashful and did not always manage to join the class activities. The Beginning of My "Activeness" Our school year was divided into three parts and we received our first school report right before New Year. One day our head teacher Freulein Rosenblum came into the classroom and said that the teachers' council met the day before to discuss our marks. She also added that Frau Berz, our headmistress who taught our class history, had been very surprised: she noticed that I had excellent marks in all the subjects except Yiddish and Hebrew. I had no mark at all in history because Frau Berz never asked me any questions since I never raised my hand "voluntarily" to answer one. Also, she must have considered me a new student and therefore decided to "spare me". I understood therefore that Frau Berz shall give me some questions to answer at the coming history lesson. This is exactly what happened. As soon as she came into the room Frau Berz called: "Eidus!" and I came up to the blackboard and replied to all her questions without a hitch. She asked me lots of questions and in the end gave me an "excellent". Only then I realized that in this school if one does not raise his hand in class it meant that he either did not know the answer or did not want to answer it. So, I started raising my hand and therefore moved from the category of "passive" students to that of the "active" ones. This change extended to after-school activities as well and I became less shy. I thus became a more "advanced" student: those of us who participated in student-administration bodies (this was a progressive school and each class had such bodies) that organized school outings, festive evenings, those who discussed all sorts of events, organized study and hobby groups, etc., were considered more advanced students. Soon enough I was being elected somewhere, I participated in a large concert doing gymnastic exercises and, generally speaking, started feeling much more confident in class. The Skating Rink - A World Apart

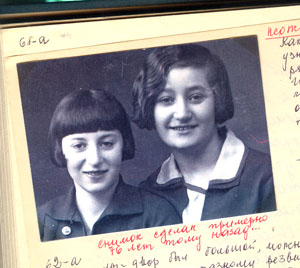

This small picture, also sent to me from Marik Yoffe, Hanze's son, many years later, reminded me of a scene connected with the other girl in the picture, Sara Zavelovich. Sara did not attend our school but a different one that was nearby and very often she used to come to our school yard, where we were all usually playing and running around.

The skating rink was a world apart. Almost the whole of our class went to skate together, we kept doing our circles along the rink for hours and after we grew cold, went into the cafeteria, drank tea and sucked on our "iriski" sweets. The skating rink was the place to conduct heart-to-heart talks, to sort out quarrels and to form new friendships. The skating was usually done in pairs or in a "snake" row, while those who were better skaters were doing their own tricks or speeding away alone. I remember how I skated with Alter Heifets. He was going through quite a emotional drama at the time: his love for Hanze Slovin was left unreciprocated. He told me about his suffering, read me the poems who had written and dedicated to her and kept saying that he will remember her forever… (In the summer of 1971 Alter Heifets and I sat on the beach in Melluzhi and shared memories about our school, Hanze Slovin and the skating rink…) Before the war Hanze married Kotka Yoffe, a fellow known in our school as an actor and a funny-man. She left Riga with her little baby, ended up in Izhevsk,where she worked in a laboratory. She was a biologist. When we all came back to Riga she became ill, she had stomach cancer. Hanze died in the summer of 1945. She was only 32… My memory now takes me back to the skating rink, to the winter of 1928. We were all so happy together, we had such fun that we did not notice the time go by. I used to come back in such a happy state that Mother never once reprimanded me for coming home late. I was always hungry after skating and the best meal was some "sitnik" (a special rye bread) with butter and smoked "stremiga", a small fish. …

|

I did not know Yiddish at all then, but Mother said

that Zyama and I will be studying it during the summer and this

will prepare us for our move to the Jewish school. So, we started

waiting for the summer to come. Finally, a Yiddish teacher, a Mr.

Berkovich, came to give us lessons. He was a fine looking, serious

man with black hair and black eyes. He taught us well and very quickly we could read and

write in Yiddish and also to speak it on some basic level. When

he arrived to give his lesson he took out his watch to mark the

time, so that he could leave right after the lesson (to run off

to his other students, as I had learned later).

I did not know Yiddish at all then, but Mother said

that Zyama and I will be studying it during the summer and this

will prepare us for our move to the Jewish school. So, we started

waiting for the summer to come. Finally, a Yiddish teacher, a Mr.

Berkovich, came to give us lessons. He was a fine looking, serious

man with black hair and black eyes. He taught us well and very quickly we could read and

write in Yiddish and also to speak it on some basic level. When

he arrived to give his lesson he took out his watch to mark the

time, so that he could leave right after the lesson (to run off

to his other students, as I had learned later).

By that time Luba Fishberg and I grew more apart and

I became friends with Hanze Slovin with whom I now shared a desk

in class. Hanze was a good student, she worked hard but she was

less talented than Luba. She was, however, one of the most "active"

girls in class, she served on all the different committees and I

respected her for that. We became friends, often did our homework

together and went to skate together. This picture was taken some time after we

finished school.

By that time Luba Fishberg and I grew more apart and

I became friends with Hanze Slovin with whom I now shared a desk

in class. Hanze was a good student, she worked hard but she was

less talented than Luba. She was, however, one of the most "active"

girls in class, she served on all the different committees and I

respected her for that. We became friends, often did our homework

together and went to skate together. This picture was taken some time after we

finished school.

I remember that it was one of the first warm and sunny

days of spring. After classes we all ran out into the school yard,

gathering in little groups and talking. One of my classmates, a

boy called Harry Finkelshtein, whom I liked very much, was there

too. All of a sudden Sara Zavelovich appeared and we were all struck

by her appearance: she was wearing a new beige-colored coat with

a belt, a straw hat with a ribbon and a flower on the side of it,

shoes with a small heel and "flesh-colored" stockings.

The boys gathered around her, everyone spoke to her and Harry was

there too, obviously interested. I suddenly realized that compared

to Sara I presented a rather sad picture: I looked like a grey little

mouse in my shabby grey raincoat, a brown "panama" hat

on my head (this was something children wore at the time), simple

cotton knee-length stockings and old black shoes. I felt very sad

and my heart fell… This episode remained in my memory forever.

I remember that it was one of the first warm and sunny

days of spring. After classes we all ran out into the school yard,

gathering in little groups and talking. One of my classmates, a

boy called Harry Finkelshtein, whom I liked very much, was there

too. All of a sudden Sara Zavelovich appeared and we were all struck

by her appearance: she was wearing a new beige-colored coat with

a belt, a straw hat with a ribbon and a flower on the side of it,

shoes with a small heel and "flesh-colored" stockings.

The boys gathered around her, everyone spoke to her and Harry was

there too, obviously interested. I suddenly realized that compared

to Sara I presented a rather sad picture: I looked like a grey little

mouse in my shabby grey raincoat, a brown "panama" hat

on my head (this was something children wore at the time), simple

cotton knee-length stockings and old black shoes. I felt very sad

and my heart fell… This episode remained in my memory forever.