The Summer of 1922CHAPTER 11 Going to the Seaside for the First Time The "dacha" or the summer house was rented that summer – in 1922 – in Karlsbad I (which later changed its name to Pumpuri in Latvian), on Line 17 (as streets were then called at the seaside), and the house stood very close to the beach of the blue sea. The house was rented for both our family and Aunt Sonya's. Moving to the seaside for the summer called for a lot of packing. The belongings were packed in large woven baskets, big parcels and, I think, suitcases. The luggage was taken over there by a horse-drawn cart and we took the train. I think the train stopped near the bridge over the river Lielupe and we had to cross the bridge to take another train to continue our journey. When during that summer we started playing a game pretending that we were travelling by train we tried to copy everything that took place during our train trip. First of all, one of us yelled "Board the train!", then there was a whistle, the train was supposed to move and someone imitated the noise it made as it as it moved off. Then tickets were checked and "passengers" left at the different stops that our train had made. We announced the list of the names of all the stops as if it was a poem (their names have changed since them from German into Latvian): Riga-Tornsberg-Zassenhof-Zolitude-Pupe-Bulli-Bilderngshof-Edinburg-1 – Edinburg-2 – Majorenhof- Dubbeln – Karlsbad -1 – Karlsbad -2- Asari -1- Asari-2 – Sloka – Kemeri. I think Priedaine is missing from this list. It was called Sosnovoye then and there was no train stop there. The German names turned into Tornjakalns and Zasulauks and Avoti, Dzintari, Mayori, Dubulti, Melluzhi, Pumpuri and Vaivari appeared too but that happened much later. The train game was great fun and it was an important part of our summertime life. … Let me now go back to the first days of our first summer near the sea. As soon as we arrived I wanted to see it. I was told that the sea is very close and I was told in which direction I should go. The path lead slightly uphill. I walked and walked for what seemed a very long time and I still did not see the sea. I felt uncomfortable all alone and turned back. They were surprised at home that I did not see the sea and the next day, when I went up there with Mother, it appeared that it was a five-minutes' walk. From the top of the little hill one could see the sea going up to the horizon. Why did the road seem so long yesterday and why did I fail to go up to the top? I felt ashamed of myself: it was a matter of a few more steps! What a summer it was! Our landlady had four or five houses which she rented out for the summer to families with children. The four of us were the youngest and there was no time to get bored. All of us got together and we spent whole days playing. I remember our summer house very well, especially the veranda with its glass windows. Some of the glass was tinted and it had a picture of a yellow sun with long rays of light. The windows were especially pretty in the evening. It was a one-storey house, but it was long, as must have been the fashion then. The veranda lead into a hall, there were small rooms on both sides of it and a corridor lead into a kitchen "in the back". Our landlady kept cows, horses and chicken and we went to watch how the cows were milked. We got on good terms with the landlady's daughters and one of them, Austra, who was my age, became my good friend. She was a nice happy girl with straight fair hair and a lovely smile. Karlsbad was, of course, very different from what Pumpuri is today. A typical feature of the area was the ruined side of the street. After all, everything was just starting to recover from World War I. Thus, when we walked along Line 17 from the road to the beach there were summer houses on one side but the other side was full of ruined houses or houses that were raised to the ground. There were some parts of walls, debris, bits of glass, hills of sand, concrete or bricks. Bushes and pine trees were growing all over the place. These ruined spaces became our playground. We used to walk around there, went down into what used to be basements, looked around on the ground and found lots of wonderful things. The most interesting of them were bullets and cartridges… We knew that they were used during the war. However, five years passed since then and the war did not appear in our games at all. It seemed a very distant event. The bullets and the cartridges were just another discovery, like a nice colored stone, a shell or some colored glass that was considered a prized possession. It so happened that the verandas of many of the summer houses built there were decorated with colored glass. The sites of the houses destroyed during the war were full of bits of that glass. We found pieces of yellow, orange, green and blue glass in the sand, the surrounding debris and in the forest and used to hold them against the sun, like some magical glasses. The world around us changed colors. Everything we found was a source of rejoicing. There was also a law: whoever found something yelled to the others: "Was hab'ich gefunden!" ("Look what I found!" in German), while the others yelled back: "Zeig'her! Zeig'her!" ("Show us! Show us!"). There was a certain sing-song to both these cries. These were moments of real discovery, of gripping "archeological expeditions" in which we engaged often and for a long time. My Second Bad Dream The "expeditions" on the other side of our street, in the forest and the empty spaces nearby are connected with my second bad dream. It haunted me for a long time. …We were doing a "khorovod" (a Russian folkdance, danced by women who move in a circle and accompany their dance by singing – Tr. ) and everything was lovely, happy and peaceful. Suddenly an enormous bird, a parrot or a kite, appeared in the sky and it was flying round and round above us. We stopped, paralyzed by fright, and saw that it was descending, coming towards us. Suddenly the bird attacked me by pecking at my left foot above the knee. I screamed with pain and horror and… woke up. It is dark. There is no-one dancing and no big bird, but the fear paralyses me. Even though my leg does not hurt but I clearly feel the spot where the bird touched me. I am scared and I am afraid to move… We Are Feeling So Insulted I have already mentioned that all of us, "the smaller children", used to play all together, we were all friendly and no-one picked on one another. I only remember one major quarrel. We were all planning to go somewhere to play, either to the forest nearby or to one of the clearings, and suddenly someone said that we are not going to take Zyama with us because he was too small. Zyama was 6 years' old then and he was a short thin boy who was considered a weak child. When the whole group decided that Zyama could not come to play, he started to cry. He sat down on the porch and cried very hard. I was so sorry for him and I felt so hurt that I sat next to him on the porch and began to cry too. While we were sitting there both crying, the other children walked around us, imitating our crying and repeating all sorts of insults. One of those children was…Yoka! That was just too much, that was an act of betrayal that lead to even more bitter tears. Then they all left and Zyama and I remained all alone on the porch… Cigarettes and Tea Memories of Karlsbad make me think of Mother's pedagogical principles, about her approach to us and our upbringing. It was based on the idea of freedom, on absence of pressure or excessive discipline. All these remained with all of us, children, influencing both our characters and our behavior. The first memorable event took place in Karlsbad that summer. It had to do with cigarettes. Yoka wanted very much to try smoking. It was, of course, strictly forbidden. Yet he kept talking about it again and again, asking permission to do so. One day Mother said that she would get him some cigarettes and he could have a smoke. She did buy them and gave them to Yoka. I remember well how Yoka, wearing an expression of great self-importance, took a cigarette in front of all the grown-ups, lit a match (he was 6 at the time) and started smoking. After he inhaled once or twice he started coughing, felt sick and had to be put to bed. I, however, "seized the opportunity": I took a cigarette and managed to smoke it all without a single cough. I was very glad that I managed to finish a whole cigarette. Yoka, on the other hand, never spoke about smoking after that and never even looked at a cigarette. He remained a non-smoker all his life (even if he did smoke a pipe from time to time). In Tamara's case, Mother allowed her "to have tea". She was usually given milk or cocoa to drink, but she asked for tea and was never allowed to have it. One day Mother said: "Sonya, why don’t you give her a cup of tea!?" We were all sitting around the table on the veranda and Mother herself poured a cup of tea from the "samovar" for Tamara. The tea was then poured into a saucer and Tamara drank saucer after saucer full of tea, until the cup was empty. She enjoyed every drop of it. Mother smiled as she passed the tea to Tamara. We were not asked to do things against our will. Maybe already then I understood that and this is why I remembered how Mother allowed both Yoka and Tamara,who was three and a half then, to have something they had long dreamed about, thus freeing them of the feeling of something being unattainable, a feeling that can become a burden on one's heart. We Are Being Photographed Some photographs remained from the period we spent in Karlsbad. (These photographs were in Tamara's possession until 1953, when they were confiscated during her unlawful arrest. ) We were photographed in pairs, according to the friendship ties between us or rather according to what the grown-ups thought these ties were: Yoka and I and then Zyama and Tamara. Both couples were supposed to be "kissing" and that's how we were photographed. Our friendships did not last too long because we all went to different schools and no longer lived together. Yoka and Zyama were friends when they were about 10 to 12, while the difference in age between me and Tamara was too large for becoming friends. There were times when we become better friends and sometimes we drew apart, but it did not last long. In any case, during that summer the friendships were what they were and I still remember those photographs. Zyama and Tamara are sitting there kissing, while our picture was different: Yoka is sitting up very straight, as if trying to move away, while I turned towards him with my lips ready for a kiss…I also remember a picture where Tamara was photographed with a huge bouquet of lilacs. It was a beautiful picture. My Wonderful Doll Is Broken Father brought this doll for me from somewhere. It had wavy hair, pink cheeks and could open and close its eyes. I do not remember what her name was, but it had a bed of its own, with a mattress and a blanket. I took great care of the doll and did not even take it outside when I went to play. The doll was kept in her bed on the floor in the corner of our children's room. One day Sonya was washing the floor and asked me to take the doll out. I took the bed with the doll to another room. When Sonya finished she told me to bring the doll back. I took the doll's bed, holding its front and back sides with my both hands and carried it, together with my doll, into our room. Suddenly the doll fell from the little bed and its head broke into bits. I cried out and my tears just flowed. I cried bitterly for a long time and just could not believe that my doll was no more. Many times later Sonya remembered how it all happened and she always said: "It was heartbreaking to listen to your crying. You cried so terribly as if a human being had died. " This was the beginning of the long story of my doll. There was a "doll clinic" called the "Puppenklinik" in German on the corner of Elizabetes st. (later Kirov St. ) and Alexander St. (later Lenin St. ). This was the place where there was once a dairy restaurant and later that spot became a hotel. My doll was brought to this clinic to be repaired. We chose a new head for her, a head that did not break. However, either because there was no money to pay for repairing it or because the matter was accidently forgotten, the doll was left in that clinic for about a year. When we finally came to pick it up it transpired that the doll had been sold. I felt my loss once again and took it very hard. We must have been short of money then and it was not possible to buy me another doll. I therefore started saving money for a new doll and that lasted for about two years. I must have been about 10 when at last Mother and I went and bought a new doll for me. The new doll, called Vera, had an unbreakable head and blond hair. Mother made a dress for her from a material in black and white checks, as well as a black apron like the ones we wore at school. Vera "lived" with me until the war and was kept in the cupboard with the other dolls which were supposed to be given as a present to Iren when she turns 4… The dolls remained in the cupboard: the war started before Iren turned 4. I left Riga on 18 of June and Iren became 4 years old on the 10 of July. My plan did not work out because of these 22 days… However, my "doll's cult" became even stronger: after my first "rag doll" that I had in Crimea, the second one that I had on the train, the third one that broke, the fourth one, Vera, stayed with me for some 17 years… Our First Apartment in Riga The Apartment at No. 25 Suvorova St. I am surprised that I still remember all those addresses. It seems to me that we did not live long at this apartment (Suvorova St. later became Krishjan Baron St. ) and we only lived there for the winter or the spring. …Across the street from our windows there was a kiosk that used to sell fruits. Zyama and I often sat near the window and looked at what was going on in the street. In the evenings the kiosk was brightly lit and we watched people enter and pick their apples and pears. One day we started playing a game: we imagined that some thieves came into the kiosk and while some of them tried to distract the salesmen the others quickly picked up some fruits, put them into shopping bags and quickly moved towards the exit. We tried to guess which of the shoppers would look like good thieves and which of them might be successful in leaving the kiosk unobserved. It turned into a fascinating game… Something Interesting at Aunt Sonya's During that winter Aunt Sonya moved to another apartment in the Opeshkins' house. Her new apartment was a large one and I loved coming there. The reason for this was the fact that Yoka and Tamara always had governesses who taught them German, English, drawing and reciting short dramatic scenes. I remember that a large performance was planned for a date in the spring and Zyama and I were supposed to take part in it too. I was to appear dressed as the Sun. A special orange dress was made for me from crepe paper and I was also to have a special headdress shaped like a sun with rays of light. The headdress was decorated with gold paper. It was all very beautiful and great fun. I used to draw together with Yoka and Tamara. Their governess was very good at drawing. When she used to correct our drawings by a few lines of her own these drawings came alive. We often drew "from nature". I remember very well having drawn Tamara's doll in a blue dress. The governess fixed up a little my drawing of the doll's face and it became a real portrait. This was a picture done in water colors. I was not as good with water colors as I was with drawing, but the governess corrected my "creation" a bit and it became very pretty. I remember that I was uncomfortable that it was not all my own work, but I was very pleased that it came out so well. Here is another recollection connected with Sonya's apartment. Our family must have been moving at the time or there was something at home because of which I was allowed to stay with Sonya for a few days. I liked it there so much that at the end of the arranged period I did not feel like going back home. Mother allowed me to stay there as long as I liked and I lived there, as far as I remember, for 6 weeks. Then one morning my nose started bleeding (this happened to me years later too). They put a metal key to the back of my head and then some cold water, but the blood was still coming and the whole towel turned red. I started crying and felt very sorry for myself. My heart was heavy and I felt rather uncomfortable. Suddenly a woman came into the room (she must have been a cook or a governess) and said: "This is God's punishment for your refusal to go home!" I did not believe her, but suddenly I felt that I wanted to go home! Until that day I did not think of home at all, after all, I saw everyone when they came to Sonya almost daily. I went home… There is something else I remember about that period. Zyama hated cauliflower (he called it "a frog") and cooked carrots. No-one ever made him eat them at home, but at Aunt Sonya's place this became a subject for discussion, especially by the governesses. They used to threaten him: "If you are not going to eat the cauliflower you aren't going to get any dessert!" This threat used to have the opposite effect on Zyama: he rejected both the cauliflower and the dessert and just would not eat. His face turned into an ironic or even a gloating grin. Our "freedom-loving" tribe could not stand any punishments and there were never any of them at home. I still cannot stand it when children are being specially punished for something…

|

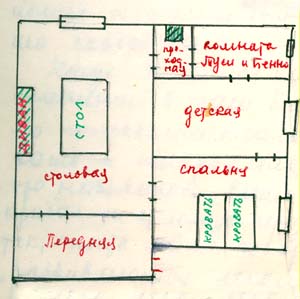

Our

first apartment was on Pakgauznaya St. (or Noliktavas iela in Latvian). This is where the tram No. 6 used to stop near the Pioneers' Palace

before the war. The apartment was a furnished one, I think. It had

four rooms and another one, a very tiny one. The rooms were all

connected. Zyama and I still did not go to school (we should have

gone really, I was already 8 by then), only Tusya and Benno did. This was the apartment where Sashen'ka was brought to after he had

been born. Tusya became a scouts' guide while we were living there

and her friends ( Roza Levin and Bronya Idelzak were among them)

used to gather there. Tusya was considered grown-up and independent

and I was still the "little one". However, I seemed to

have developed a talent of some sort: I started to play chess and

Benno used to teach me. He played with me in that tiny room we had. He used to explain the moves to me very patiently and he was very

glad that I understood it all so well. I treasured those chess games

with him…

Our

first apartment was on Pakgauznaya St. (or Noliktavas iela in Latvian). This is where the tram No. 6 used to stop near the Pioneers' Palace

before the war. The apartment was a furnished one, I think. It had

four rooms and another one, a very tiny one. The rooms were all

connected. Zyama and I still did not go to school (we should have

gone really, I was already 8 by then), only Tusya and Benno did. This was the apartment where Sashen'ka was brought to after he had

been born. Tusya became a scouts' guide while we were living there

and her friends ( Roza Levin and Bronya Idelzak were among them)

used to gather there. Tusya was considered grown-up and independent

and I was still the "little one". However, I seemed to

have developed a talent of some sort: I started to play chess and

Benno used to teach me. He played with me in that tiny room we had. He used to explain the moves to me very patiently and he was very

glad that I understood it all so well. I treasured those chess games

with him…