I Am Joining IrenCHAPTER 3 When it became clear that the group of Pioneers will not be able to travel to the Artek summer camp I gave K. Voronkov the money I had been entrusted with: the sum of nine thousand Roubles. He put them away into the safe. Now, when I came to inform him that I will be leaving Moscow he asked me: "What about money? Do you have any money?" I had very little money and I told him so. "What about clothes?" – he asked. I just indicated that the clothes I was wearing were all I had. He went up the safe in his office, took out a thousand Roubles and handed them to me. "Go and get yourself the things you really need" – he said. We parted and I left. I was really thankful to him for his care: I really did not have anything. Then came the "shopping spree" and this is what I bought: a suitcase (the wide black one, which we always used for taking things down to the 'dacha'), a blue woolen cardigan (which was stolen from me at the Prechistoye railway station), two summer dresses, a blue one with white dots and a red one with white dots (I wore them for years), some underwear, a pillow and some little things like needles, threads and a thimble (I still have it). I also wanted to buy a pair of scissors, but it was impossible to find them anywhere in Moscow, I looked everywhere for them. I also remembered that Iren did not have any shoes as her little shoes remained under a chair in the Komsomol Central Committee office. I bought her a pair of yellow 'valenki' (felt boots). She wore them through all the years of the war and later on even Tusya, my daughter, wore them a little. I felt I was really "well equipped" now, especially as I still had five thousand Roubles left. I then went to the railway station to buy the train ticket. I came up to the ticket office and said: "Would you please give me a ticket to the Kozy station?" The woman took some sort of a long list and said: "There is no such station, there is a station called Kozye." "Then give me a ticket to that station, " – I decided on the spot and got my ticket. It transpired later how inexperienced I had been. So, here I was on the train and it became clear that I shall reach Kozye only on the next day, somewhere around 6 o'clock in the afternoon. The railway carriage was full of people, there were many women and children…I spoke to some of the passengers and asked them where they were going and why… There was an old woman in our carriage who was travelling with a little girl. I played with the girl a little and the old woman asked me where was I going. "I am going to Kozye" – I said. "Never heard of that but I do know where Kozy is!" she said. I felt all cold inside and even my heart seemed to have stopped beating. "And where is that?" – I finally managed to say. I had a feeling that I might somehow interfere with her reply. She told me that to reach Kozy I had to get off at the Prechstoye station and then make my way to Kozy, a village about 25 kilometers away. We were supposed to reach Prechistoye later in the evening. It also transpired that Kozye was in the Vologda region while Kozy is a small village and it is not on the railway maps since the train stops in Prechistoye only… I would have of course reached Kozy anyhow, but it would have taken lots and lots of efforts and inconvenience, as well as lots of lost time. What I should have done back in Moscow was to go up to the information office and ask them a reasonably presented question… Now I was sitting on the train thinking about it all and feeling extremely happy that an accidental conversation with that old woman made my search for the place where Iren was so much simpler. We reached Prechistoye by night-time. When I asked at the station how could I make my way to Kozy they told me that I had no choice but to sleep at the station and then in the morning I might find a cart heading in that direction. I spent the night at that small train station, sitting there with my suitcase and falling asleep from time to time. At six o'clock in the morning I starting looking for someone who could take me to Kozy and I found someone who was going to take some hay over there. So, I came along together with my suitcase. … The horse trudged along slowly and the 25 kilometers seemed endless. When I came into the hut and hugged my Iren it seemed that I will never be able to tear myself away from her… I still have a notebook with some notes I wrote during those years. (The notebook was in my bag when I left for Moscow on 18th of June.) Here is what I wrote on the 3rd of September 1941, some months after the events I am referring to here: "After spending three weeks in Moscow I found Iren in a kolkhoz. When we met that evening she was already in bed. While kissing me she asked: "Why did you leave without me? Don't do that again as another war might start and we shall again lose each other!" I promised that I will never go anywhere without her, but in 1943 I was sent to a place called Mengery and I had to leave without Iren. In 1948 I went for a vacation to the south, also without Iren. On both occasions I was worried about leaving her behind. In that hut, where Bertochka and the children were living, there were also other people. Everyone slept on the floor on piles of hay and only Iren and Yasha slept in some sort of a small bed. Everything there seemed unusual to me. In the morning the adults went to work in the kolkhoz and only Bertochka and an elderly Jewish man named Magidson remained at home. Bertochka was very deft in using the long 'oukhvat' (an oven fork) for putting pots with 'kasha' (porridge) into the large oven and taking them out. I was surprised to see how quickly she adapted to the situation. She seemed to know everything: where and how one could obtain bread and grain, how to stoke up the oven, etc. I was sure that I would have never managed as well as she did. The villagers looked at Yasha and Iren as if they were some sort of miraculous creatures. Yasha had light hair and blue eyes and Iren had brown eyes and dark hair. Both children had long hair. When referring to Iren they used to say: 'She has long hair like an adult" because all the village children had their heads shaven or cut very short. The two children dressed in the kind of clothes children wore in Riga looked very unusual there. … It so happened that I found an opportunity to move to the town of Yaroslavl. I thought I might find work there. So, we started making preparations to leave. I left Bertochka half of the things I had bought in Moscow, the clothes that could fit Yasha and half the money I still had. Now we had to find a way to make our way to Prechistoye, to the railway station. I learned that carts with bales of hay were being loaded up in the evening and very early in the morning, when it was still dark, they left for Prechistoye. I "boarded" such a cart together with Iren and our suitcases. The "driver" was a 13 years'-old boy and I noticed that he kept dozing off every now and again. I was afraid he would fall asleep and the whole cart will end up in a ditch. I kept asking him: "Are you asleep yet?" "No-o!" he replied. Off we went moving to and fro according to the horse's gait. I must have fallen asleep at some stage, because I suddenly woke up hearing shouting, something snapping and finding myself under piles of hay! Oh horror, where was Iren?! Suddenly I heard her whining voice: "Mum, I am here!" I managed to find her in the dark, pulled her out from under the hay and found our suitcases. The boy driver managed to lead the horse and the cart back to the road and he started putting the bales of hay back. We went back to the cart and reached Prechistoye without any more adventures. We reached it when it was still a long time before the train to Yaroslavl was supposed to stop there. I put Iren to sleep on one of the benches at the railway station and said: "You better go to sleep now, little girl!" She asked me: "Is this now our home?" – "Yes, my child." She slept a little and then the sun came out. It became quite warm and we left the railway station and found a grassy clearing not far away. I must have been very tired for after putting Iren to sleep and covering her up I put my blue cardigan bought in Moscow under my head and immediately fell asleep. There were two suitcases next to me: the one I brought with me from Moscow and the one Bertochka brought with Iren from Riga. It had inside all the necessities, even a glass for cleaning her teeth, her pink blanket, her winter coat, etc. After a while I woke up with a jolt and saw Iren still asleep and our suitcases. The only thing missing was my blue cardigan: someone must have pulled it out from under my head. I was glad it was just that: we could have been left without a thing! At that time I could not imagine that something like that could happen, so I went off to sleep with our belongings next to me… Yaroslavl I do not remember any scenes connected with our arrival at the Yaroslavl railway station and I do not remember how we made our way to the "evakopunkt", the evacuation centre where the barracks housing the evacuees were located. We boarded a local train and went to one of the city's outer suburbs, Vspolye, to reach the "evakopunkt". I saw the central part of Yaroslavl later. I still have pictures of the main train station and of the Hotel "Yaroslavl".

According to my notes made during that period, Iren was sick during our trip from the village of Kozy to Yaroslavl. She had high temperature and after we arrived in Yaroslavl she was still sick for another week. She stayed in bed in our barrack, absolutely alone, while I went into town to try to make arrangements for finding work, etc., and when anyone came into the room, a nurse or a woman neighbor from the next barrack, Iren used to speak to them: about me and my work, about Riga, about Berta, about our trip on top of the cart carrying hay, etc. When I came back I used to get compliments about Iren, about the way she spoke, nicely and clearly, and how well she told all her stories. During my trips into town I had no time, nor was I in the mood, to see the sights, but I did see some of it. Now when I look at these photographs, I remember some of the streets. I wanted very much to find work in Yaroslavl, but that proved to be impossible. Here is a picture of the Volga embankment and of the local Drama Theatre.

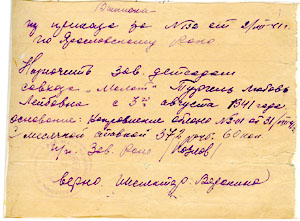

I finally received a job as kindergarten director at the 'sovkhoz' (collective settlement) "Molot" ("Hammer"), located some 12 kilometers away from Yaroslavl. The part of the sovkhoz where I was to work was called "Smena" ("The Next Generation") was another 5 kilometers away. It read as follows: "Excerpt from Order No. 132 of the 2nd of August 1941. The Yaroslavl Regional Education Department. Turgel Lyubov Leibovna is to be appointed as kindergarten director of the sovkhoz Molot as from 3rd of August 1941 with the monthly salary of 372 Roubles and 60 Kopecks. An appropriate document (No. 2-01) shall be issued on 31st of August 1941 by the District Education Department.

|

Here I am wearing one of those dresses bought in Moscow in 1941. The picture was made in 1945 when I was back in Riga and when I came to Lankstini, to visit Leibele Futlik in his army camp. Zyama made this picture which I always liked very much.

Here I am wearing one of those dresses bought in Moscow in 1941. The picture was made in 1945 when I was back in Riga and when I came to Lankstini, to visit Leibele Futlik in his army camp. Zyama made this picture which I always liked very much.

The following is an excerpt from the order confirming my appointment. This is what war-time office communications looked like.

The following is an excerpt from the order confirming my appointment. This is what war-time office communications looked like.