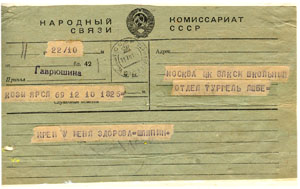

Life in Moscow, 1941CHAPTER 2 My life become divided into two or even more parts. The following days were filled with all sorts of endless attempts to fix things. I visited the children in their dormitories. They were worried by the fact that they have not yet been transferred to the Artek summer camp. They were not yet told anything about the war. In the meantime, officials kept promising me at the Komsomol Central Committee to use their authority and find a way to send me home. They even permitted me to send telegrams to Latvia through special channels. I did that and in the meantime I had to live somehow. Aunt Frieda started to feel concerned that I have been staying in Moscow for so long without a residence permit ("propiska" in Russian) and I therefore requested some Central Committee officials to help me with this matter. They gave me a document stating that I have been working at the Pioneers' Palace in Latvia and that I have been sent to Moscow to accompany a group of children proceeding to the Artek camp. The document was signed by Konstantin Voronkov, the Deputy Head of the Schools and Pioneer Organizations Section at the Komsomol Central Committee. Voronkov was a very kind man who tried very hard to help me. I do not know what he knew or did not know at the time. I had a similar document issued by the Director of the Riga Pioneers' Palace a few days before I left. It was translated into Russian in Moscow and after having submitted both these documents to the police office I received a residence permit valid for a month. This gave me time to find out what to do. Every day I hurried to get to the Komsomol Central Committee offices in order to find out whether there had been any news for me, but there was nothing… I tried to find something to fill up my days. I went to the All-Union Agricultural Exhibition and found it to be something grand. There I saw the sculpture "The Worker and the Farmer Woman" about which I had heard in 1937, when this sculpture by V. Moukhina had been exhibited at the World Fair in Paris. Then one day on my way home I noticed on Gorky St. a small sign saying "The Museum of N.Ostrovsky". I went inside and looked at the exhibition. It seemed that this visit transported me back in time, when we, members of the underground, read in secret Ostrovsky's novel "How Steel Hardened". I visited the Tretyakovskaya Gallery housing classical Russian and Soviet art. I bought a set of postcards of paintings by classical Russian painters which I still have. Soon both the Mausoleum and the Gallery and many other places were closed to the public. I finally decided to visit the offices of the Latvian diplomatic mission and try to find out what was going on. I met with a Comr. Bernshtein who had heard me out and then said in a rather surprised or even irritated tone: "Either you are plain stupid or you really don't understand anything! The territory of Latvia has been occupied by the Germans! Trains with people leaving Latvia are moving out of the country into Russia… Many of the trains have been bombed by the Fascists… And here you are talking about going back home?! They were simply misleading you at the Central Committee! Leave Moscow immediately, you have no business of being here!" I merely tried to ask him: "And what about my daughter? Where is she?" "How should I know where she is? Just leave!" – he said. "Where are the trains going?" – I asked. "To Ivanovo, to Kirov, to Chuvashia! Just go!" I merely asked to be allowed to until my Moscow residence permit runs out. Moscow was being bombed quite a lot by that time. When I stayed with Frieda I went down to the bomb shelter together with everyone else when we heard the sirens. I did not feel any fear and in order to fight the boredom I started knitting something small for Iren. So, I sat there in the shelter knitting and thinking my own thoughts, waiting for the all-clear signal. During the day I kept visiting the Komsomol offices and the diplomatic mission… My Pioneers heading for Artek had left Moscow a long time ago, first for some place near Moscow, then to a place near Stalingrad and further away, for Altay. I learned about this much later. I was getting close to the end of my stay in Moscow and I kept thinking about where to go. These thoughts were terribly naïve: I decided to look for Iren in those places where the trains from Latvia were supposed to arrive. I did not even know how many such places I had to visit: five, ten, twelve… I thought I will board a train and go there to look for her… Then one day I came once more to the Komsomol Central Committee office and told Comrade Voronin that I was planning to leave Moscow. Suddenly he looked at me and said: "Wait, wait, I think there is a telegram for you here!" He went off somewhere and came back, handing me the telegram. Its distorted text nevertheless filled me with happiness to the brim. It said: "The USSU Communications Commissar's Office. From: Kozy, Yaroslavl. Oblast. To: Moscow, the All Union Lenin-named Komsomol office, the School Section. For Luba Turgel. "IRA, BERTA, I ARE IN YAROSLAVSKAYA OBLAST. REGIONAL P.O.B., SCHOOL. SHLYAPIN." I ran to the post office and sent off a telegram to Shlyapin. I do not remember what my telegram said, but the reply I received said: "The All-Union Communications Commissar's Office. From: Kozy, Yaroslv. Gavryushina. To: Moscow, the All-Union Lenin-named Komsomol office, School Section. Luba Turgel. I have no words to describe what I felt and what I thought when I read this telegram. I received in on the 11of July 1941, it said so on the stamp. For three weeks I walked around as if living in a dream, in some unreal world, filled with fears and absence of any information, suffering from terrible loneliness and despair, hoping and praying for a little bit of good luck… And here I saw short and clear words bearing the happy and joyful truth: "Iren is with me. She is well…" This was a return to life.

I learned much later how Iren was brought out from Riga. I shall now describe how it happened.

|

I also had another important document with me: my Komsomol membership card. Right before my departure from Riga the local Communist party committee approved my candidateship for party membership. On the Wednesday I left I was supposed to go to the offices of the regional party committee to obtain official confirmation. However, at the Komsomol Central Committee offices they said: "Never mind, in ten days' time you will come back and you'll get your candidateship confirmed at the next party meeting…" Almost a year had passed until I was voted on once again as a candidate for party membership. This took place when I was living in Kirov. I have kept my Komsomol membership card all these years as all these years prior to my return to Latvia I worked in the Komsomol system.

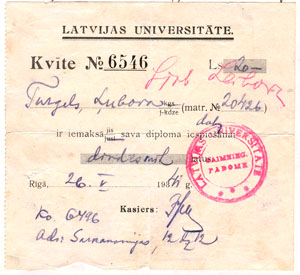

I also had another important document with me: my Komsomol membership card. Right before my departure from Riga the local Communist party committee approved my candidateship for party membership. On the Wednesday I left I was supposed to go to the offices of the regional party committee to obtain official confirmation. However, at the Komsomol Central Committee offices they said: "Never mind, in ten days' time you will come back and you'll get your candidateship confirmed at the next party meeting…" Almost a year had passed until I was voted on once again as a candidate for party membership. This took place when I was living in Kirov. I have kept my Komsomol membership card all these years as all these years prior to my return to Latvia I worked in the Komsomol system. At the diplomatic mission office they also gave me a document certifying that I had graduated from the Latvian State University. The document was issued because I had found among the papers in my handbag a receipt dated the 25th of May 1941 and stating that I had paid the sum of 20 Latts for my university diploma. When I graduated in 1939 I did not have the money to pay for my diploma and I finally did so at the end of May 1941. Having this receipt in my possession served as the basis for the document certifying that I had received a university degree. This became very important because I received a higher salary both during my work in the kindergarten and in the orphanage. I obtained my diploma in 1945 in Latvia.

At the diplomatic mission office they also gave me a document certifying that I had graduated from the Latvian State University. The document was issued because I had found among the papers in my handbag a receipt dated the 25th of May 1941 and stating that I had paid the sum of 20 Latts for my university diploma. When I graduated in 1939 I did not have the money to pay for my diploma and I finally did so at the end of May 1941. Having this receipt in my possession served as the basis for the document certifying that I had received a university degree. This became very important because I received a higher salary both during my work in the kindergarten and in the orphanage. I obtained my diploma in 1945 in Latvia.  I could not understand much from the text, but I did understand that Shlyapin managed to leave Riga and that he was telling me something about Iren. The text of the telegram was distorted and I deciphered all of it much later.

I could not understand much from the text, but I did understand that Shlyapin managed to leave Riga and that he was telling me something about Iren. The text of the telegram was distorted and I deciphered all of it much later.